It’s July 1945, and war devastates half the planet. Casualty numbers climb into the tens of millions. America, the United Kingdom, and China collectively demand that Japan surrender, or face “prompt and utter destruction.” Japan refuses. In a few weeks, America brings the promised atomic apocalypse to Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In Hiroshima, brilliant light floods the sky, followed by thunderous booming. 30 percent of civilians are killed instantly by the blast and subsequent firestorm. Another 30 percent or so are left injured. When the sky falls, it is black and radioactive. Japan surrenders three days later.

The full impact of the A-bomb is invisible. Radiation-induced cancer has a minimum latency period of five years. Some devastations are ear-splitting; this one stays quiet. One unforeseen victim is Sadako Sasaki, a twelve-year-old girl diagnosed with leukemia in 1955. During her hospital stay, she takes a vested interest in origami, making hundreds upon hundreds of paper cranes in the span of a few months. Legend states that anyone who folds a thousand cranes will have a wish fulfilled by the gods, and she wants to live. We all do.

Origami has roots in both the Allied and Axis powers. Some historians contend it bloomed from Chinese paper-folding; others insist the art form originated from religious ceremonial practices in Japan. Still, it’s not until the nineteenth century that the mathematics of origami becomes a topic of wide interest.

There are seven axioms that govern its underpinnings. The first is straightforward enough. Take a piece of paper, choose any two distinct points, and there is some unique fold that passes through both. The second axiom: take the same piece of paper, choose any two distinct points, and there is a unique fold that places one onto the other.

The rest of the axioms follow in similar fashion. Maybe all this is to say, like the points on the paper—no matter how far apart we are, we will always be more connected than we think.

Every high school freshman is familiar with the classical tools of geometry: the straightedge and compass. One for edges and one for curves.The universe of a ninth-grade math classroom can be spun with two instruments.

But not every geometric question can be answered with these two instruments. Take the Delian problem. Here’s how the story goes. Citizens of the ancient island of Delos—a small barren rock nestled in the Aegean sea—consult the Oracle of Delphi. They’re desperate; an apocalyptic plague sent down by Apollo has decimated their population. In response, the Oracle informs them that they must double the size of their altar, a regular cube, to Apollo. A trio of ancient mathematicians—Eudoxus, Archytas, Menaechmus—discover solutions, but not through geometric means. They are reprimanded by Plato, but he, too, cannot solve the riddle.

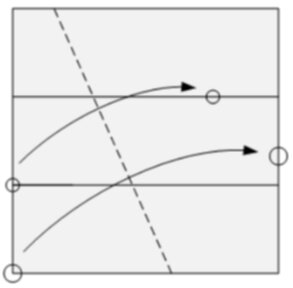

Thousands of years later, in 1837, French mathematician Pierre Wantzel proves that it is impossible to double a cube with only a straightedge and compass.So we turn to origami, which makes quick work of the task. First, fold a square into thirds. Next, sweep the bottom-left corner up to meet the right edge, so the two—thirds line brushes against the one-third line. (See the diagram below.) The point where corner meets edge divides the side of the square, such that a cube with an edge the length of the longer portion will be double the volume of a cube with an edge the length of the shorter portion.

Sometimes we need unconventional methods to construct the world. Sometimes we need unconventional methods to destruct it.

In November 1954, Sadako Sasaki’s team, the Bamboos, wins a relay race at school. When she comes home exuberantly, she notices that swellings have surfaced on her neck. Over the next several weeks, her face puffs up like a mumps victim’s. By January, red and purple spots dot her legs. The diagnosis: leukemia, the aftermath of radiation exposure. By the time she’s admitted to Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, her white blood cell count is six times higher than average.

At Hiroshima Red Cross, she meets Kiyo Okura, her roommate. Kiyo introduces her to origami, and soon, Sadako makes cranes out of all materials she can obtain—medicine and wrapping papers, cellophane. As she steadily cultivates hundreds of cranes, they dwindle in size; she uses a needle to crease them. Colorful birds pepper the windowsills and nightstands of hospital patients.

According to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, her father recounts, “We warned her, ‘If you keep up that pace you'll wear yourself out.’ Sadako continued to fold, saying, ‘It’s okay, it’s okay. I have a plan.’ You could feel the intensity of her desire to live in the way she threw herself into folding.”

Perhaps we can map Sadako’s wish for survival in the folds that traverse each sheet of paper. If the origami is flattened, these lines create a “crease pattern”—a diagram of folds that transform a slip of cellophane or gift-wrap into a butterfly, a cup, a crane.

One of the most important questions in origami math is whether a given crease pattern can be translated into a flat model, or an origami creation that can be pressed flat without deforming. This is an NP-complete problem, where NP stands for “nondeterministic polynomial time.” In short, while a solution to an NP-complete problem can be verified easily, it’s impossible to generate a solution to an NP-complete problem through mathematical means. Given any crease pattern, it’s easy to check that it can be made into a flat model. But devising a crease pattern that can be folded to a flat model proves to be so difficult, a computer can’t do it.

Flat models matter because origami is more than art. In the days before GPS, maps were folded using an origami tessellation, the Miura-ori. Parallelograms tiled the page, rendering it simple to furl and unfurl. This design was also used to bring solar panels into outer space; every solar cell was a parallelogram, painstakingly arranged to resemble a six-sided flower.

Still, origami mostly boils down to survival. Folding techniques derived from origami math have been developed for car airbags and collapsible stents (a small tube inserted into clogged arteries to encourage blood flow).

One notable recent development is led by MIT professor Daniela Rus, whose team has designed a small, ingestible bot that unfolds itself from a capsule of ice. This bot can then tend to internal wounds or dispose of swallowed batteries.

Another application of origami arises in architecture. Researchers from Georgia Tech, University of Tokyo, and UIUC have build the 3D zipper tube, which consists of interlocking slips of paper glued together in a zipper-like fashion. Highly resilient and easy to produce, these tubes can be adapted to various environments, suggesting possibilities for emergency shelter in natural disasters.

Sadako Sasaki passes away on Oct. 25, 1955, but her legacy resonates for decades after. Her classmates raise funds to build a memorial to honor her and other child victims of the atomic bombing; in 1958, a statue of Sadako holding a golden crane is completed. In Japan, on Obon Day, people fold cranes to honor their ancestors’ departed spirits, and every year, a flurry of paper birds descend onto Sadako’s statue.

Origami has lived on for centuries not for its scientific applications, but for its ability to cultivate community and creativity. It whispers legends to those who need them most and sprinkles color in hospital beds. It reminds us of the cost of war. It has helped us survive, long before it was brought into the laboratory.