Economists have the distinction among scientists of not being able to run experiments; experimentation is generally too expensive or politically infeasible. To deal with this, economists use the data available to them, often in fiendishly clever ways. One of the most clever of these ways is the method of instrumental variables.

In 1998, economists Joshua Angrist and William Evans wanted to measure the effect of having children on a woman’s employment. Now, to be clear, it’s empirically true and easy to check that women with two or more children are less likely to work. However, Angrist and Evans wanted to test if having more children caused women to work less. This is a much more difficult question to answer. For example, it’s possible that the causality runs the other way, that is, working less causes women to have more children. It’s also possible that some third variable causes women to both have more children and work less.

To measure the desired effect, Angrist and Evans studied women with two children of the same sex. At first, this might seem odd. Why do the children have to have the same sex? This doesn’t seem to affect employment decisions at all. Yet here lies the genius of the instrumental variables approach. The variable for having children of the same sex is called the instrument. As it turns out, empirical data shows that having two children of the same sex increases the chance of having a third child by 6 percentage points, perhaps because of the desire to balance the ratio of sexes. Thus, having children of the same sex does in fact affect employment, because it affects the chance of having a third child, and that affects employment. The key assumption of the instrumental variables approach is that it doesn’t affect employment in any other way. All in all, this is a reasonable assumption.

Let’s figure out exactly what’s going on here. How many children a woman has clearly affects her employment status. However, we can’t just directly compare women with two or more children to women with one or zero, since the data might be biased. For example, women with more children are older on average. Since a woman’s age plausibly has effects on her employment status, this would bias the final estimate.

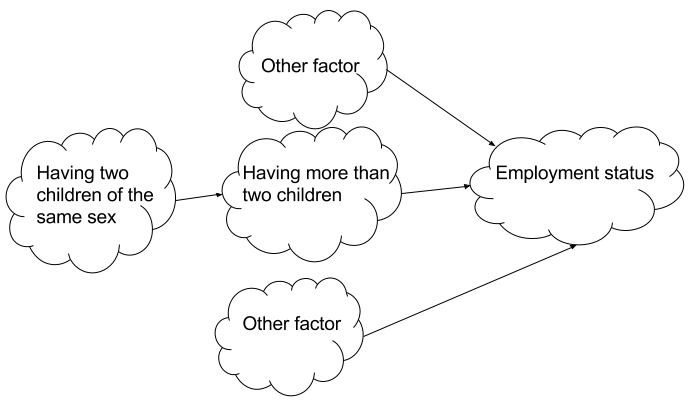

However, we just noted that a woman having two children of the same sex does affect her employment status but only insofar as it affects her likelihood of having a third child. This is called the exclusion restriction. The figure below helps explain this phenomenon:

So, while it’s impossible to directly measure the effect of having three or more children on employment, we can directly measure the effect of having two children of the same sex on employment. Using this, Angrist & Evans managed to tease out the desired effect. With this strategy (and just a bit of technical jargon), they concluded that a woman having more than two children decreases the chance of her working by about 13.3%.

Here, we used children of the same sex to see whether having more children affects likelihood of employment. This instrumental variables approach can be used in a variety of surprising ways, many others of which are detailed here. Some of the intriguing examples from the link include using the natural boundaries determined by rivers to see whether school choice affect school quality, and using electoral cycles in police hiring to estimate the effect of police on crime.

The instrumental variables approach is one of many clever methods economists have come up with to analyze natural data. Since it’s politically infeasible (and a logistical nightmare) to randomly choose people to, say, receive the minimum wage, economists simply can’t run experiments like other scientists. The real world is not a lab—that is, of course, unless you’re clever enough to make it one.