“Ambition, Distraction, Uglification, and Derision”—according to the glum Mock Turtle from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, these are the four different branches of Arithmetic which he learned in a school under the sea. If we took these pearls of wisdom for face value, clearly the MIT Math Department is missing some key courses in their curriculum. Thankfully, nothing in Wonderland can or ought to be taken at face value.

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, a man more commonly known by his nom de plume, Lewis Carroll, was a lover of riddles and wordplay; he weaved both of these elements heavily into his works of English literature, perplexing and knotting the minds of readers for generations to come. During working hours, however, the well-known author was actually employed at Oxford as a mathematics professor. A dedicated lecturer and rather conservative mathematician, Dodgson possessed a fondness in particular for Euclidean geometry and symplectic logic.

Some of his simplest logical playthings can be found in the text of the Alice novels themselves. Most of them remark upon the oddities of our common language; for example, the famous quote of when Alice says she means what she says:

"[Y]ou should say what you mean,' the March Hare went on.

'I do,' Alice hastily replied; 'at least—at least I mean what I say—that's the same thing, you know.'

'Not the same thing a bit!' said the Hatter. 'You might just as well say that "I see what I eat" is the same thing as "I eat what I see"!'

'You might just as well say,' added the March Hare, 'that "I like what I get" is the same thing as "I get what I like"!'

'You might just as well say,' added the Dormouse, who seemed to be talking in his sleep, 'that "I breathe when I sleep" is the same thing as "I sleep when I breathe"!'"

This is a simple issue of mistaken reversal; the converse of a statement is not equivalent to the original statement, a concept which poor Alice then gets lectured thoroughly in by the mad tea-party-goers. Throughout her travels in wonderland, Alice’s mind twists around many a similar puzzles of wordplay, from talk of a “treacle well” to the famous conundrum of a raven and a writing desk. Expanding upon his nonsensical universe, Dodgson also penned a set of seven poems called “Puzzles from Wonderland,” along with seven more poems known as “Solutions to Puzzles from Wonderland,” which feature riddles abound.

Admittedly, the dreamy world of Wonderland hardly showcase Dodgson’s full range of challenging and entertaining logic puzzles; his more complicated ones lie in the area of symplectic logic and are often delightfully inane. We can introduce an example of one here. Find appropriate the conclusion to:

- (a) All mathematicians have illegible handwriting.

- (b) Nobody is despised who can ride a shark.

- (c) People with illegible handwriting are despised.

How do we come to an answer for this puzzle? Well, let our statements be rewritten as implications. The subject of these sentences are people; let us take the world as the set of all people. Then we mark

- (M) It is a mathematician.

- (S) It can ride a shark.

- (L) It has legible handwriting.

- (D) It is despised.

as different statements where “it” refers to a general person. Then our three statements become

- M -> ~L (If it is a mathematician, then it does not have legible handwriting.)

- S ->~D (If it can ride a shark, then it is not despised.)

- ~L->D (If it does not have legible handwriting, it is despised.)

where ~ means “not.” Then we chain these together, recalling that any implication is the equivalent of its contrapositive: : M->~L->D->~S. Hence, we conclude: if it is a mathematician, it cannot ride a shark; or more sensibly, no mathematician can ride a shark. And this is, in fact, a true conclusion—I’ve personally verified with many Course 18s.

While Alice is not so far down the rabbit hole to have to deal with contrapositives herself, some scholars interpret some of the imagery and events in her wanderings as Dodgson’s critique of 19th century mathematical developments. The absurdity of Wonderland was possibly a reaction to the increasing abstraction of the discipline, most poignantly illustrated in how the Cheshire Cat can vanish into thin air leaving nothing but an eerie grin.

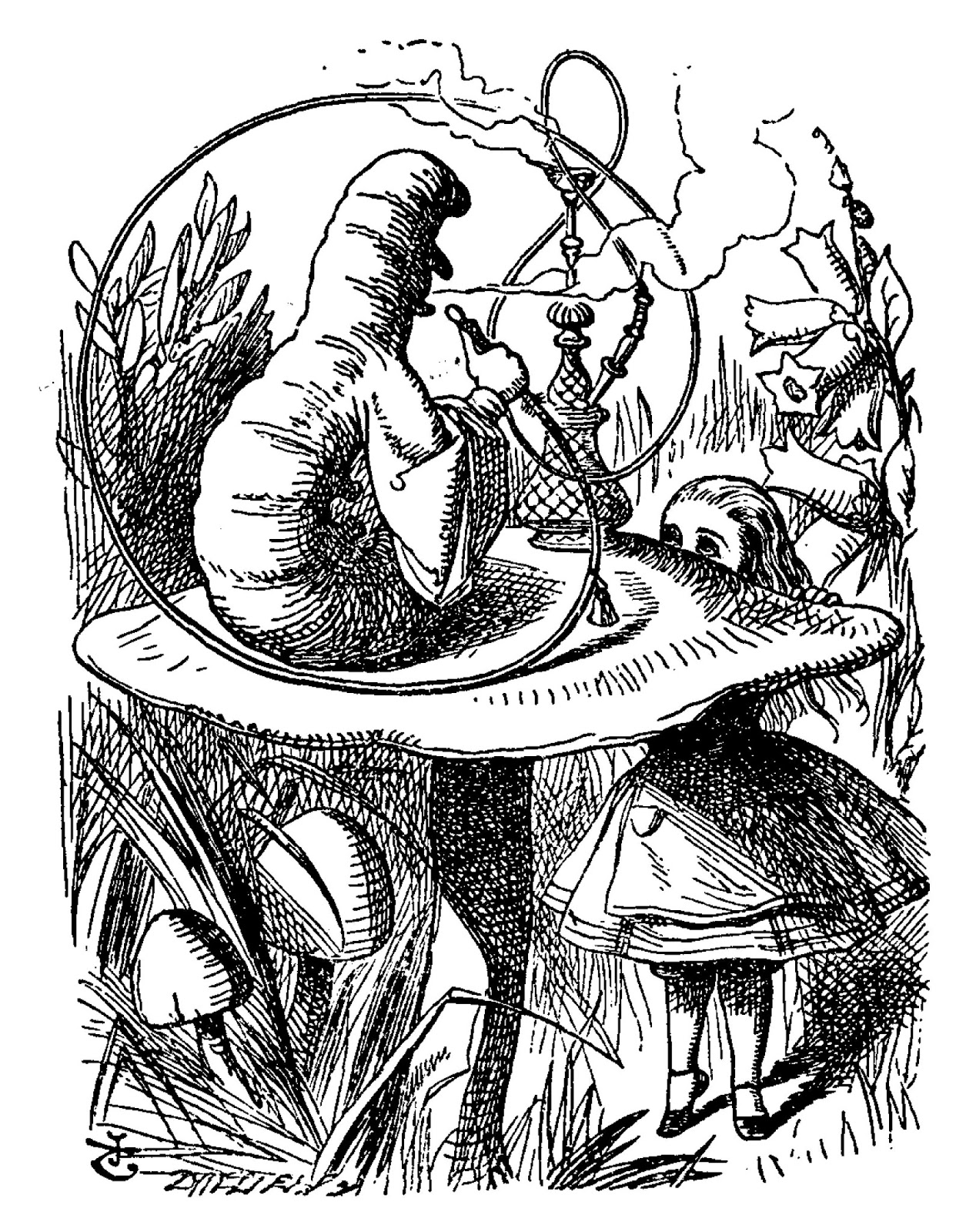

Dodgson, for example, found symbolic algebra absurd; the development of maths beyond basic arithmetic moved research further and further away from physically grounded ideas and onto nonsensical concepts like imaginary numbers. Wonderland similarly has a thin grasp on numbers themselves, as Alice shrinks and grows in height constantly depending upon what she intakes. The hookah-smoking blue caterpillar warns Alice to be careful at least about her ratios, if not her actual magnitude: “Keep your temper.”

Figure Hookah and magic mushrooms and mathematics! Harking back to a previous scene, we can also draw analogies between the mad tea party and William Rowan Hamilton’s system of quaternions, a number system that extends complex numbers to four terms instead of two. Historically, Hamilton spent a long time toying around with three terms, one for each dimension of space, but could only get them to rotate in 2-D space. He finally found 3-D rotation when he added an extra fourth term; he eventually interpreted this term as time. Going back to the tea party (or shall we say “t-party”), we have three players, the Mad Hatter, the March Hare, and the Dormouse, rotating around the table waiting for their fourth guest, Time, to show up—see the analogy?

Ultimately, the absurdity of Alice’s strange Wonderland is built upon the solid logical foundations of mathematics; similarly, the hard rationality of mathematics are not without a touch of nonsense if you’re willing to indulge in some riddles and good humor. Dodgson possessed a uniquely witty spirit and a rigorous mind, and so produced one of the greatest and most delightful works of English literature of his time. After all, he himself voiced it through the Hatter—all the best people are just a touch mad.